Most people only see weeds or wildflowers, but some of us see a creative opportunity.

Last week, we learned about Coreopsis tinctoria, also known as dyer's coreopsis and since there were a great number of flowers in the field that I photographed, I thought we might as well have some fun.

In earlier days, this was an important dye plant for coloring yarn. Up until about 1850, all color on fabric was from natural sources. When the first synthetic dyes were produced, industry abandoned these sources for the cheaper and easier chemical versions. Unfortunately, chemical dyes contain many caustic ingredients harmful to the environment and human health. The disposal of the byproducts of yarn and fabric dyeing contaminate groundwater and have an adverse impact on the ecosystem. It is thought that only one in four people in China actually drink uncontaminated water due to that country's casual attitude toward waste disposal. Things are somewhat better in the western world with strict rules for neutralizing any chemical waste produced during manufacturing, but we still have a long way to go as well.

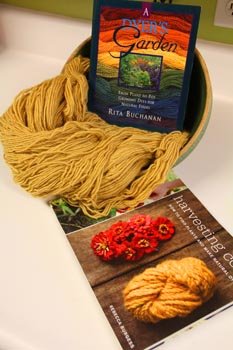

I'm quite familiar with synthetic dyes and use them often, but am always interested in learning a new skill. I've even collected a couple of books on the natural dye process, but have never put the information to the test. These little yellow flowers were a push in the right direction. I even had some natural wool yarn that I purchased some time ago in the event that the urge struck me. There are a number of places that you can order beautiful yarns for dyeing but I've used Dharma Trading for years for other craft items and they've always done a wonderful job. They even have prepared natural dyes and mordants available in case you don't have natural dye sources available to you.

I'm quite familiar with synthetic dyes and use them often, but am always interested in learning a new skill. I've even collected a couple of books on the natural dye process, but have never put the information to the test. These little yellow flowers were a push in the right direction. I even had some natural wool yarn that I purchased some time ago in the event that the urge struck me. There are a number of places that you can order beautiful yarns for dyeing but I've used Dharma Trading for years for other craft items and they've always done a wonderful job. They even have prepared natural dyes and mordants available in case you don't have natural dye sources available to you.

The first thing on the agenda was to pick enough flowers to make a proper dye. The recipe in the books indicate that a 1:1 ratio of fabric weight to flowers is correct for the coreopsis, so that turned out to be an ice cream bucket about 2/3 full. This takes a little over an hour to pick enough flowers to dye one skein of yarn. As I sweated in 90 degree heat and battled mosquitoes, I had a greater appreciation for what my ancestors went through just to bring a little color into their lives. It is also important to be a good steward of the land when collecting dye materials. Never strip an area of a plant and always leave plenty to reseed. A good rule of thumb is never take more than 20% if the plant is growing in abundance and only take 10% if you are not sure. Never harvest an endangered or threatened plant for any reason, so be sure of your identification skills. The only plants where it is ok to harvest more would be invasives, such as purple loosestrife. Always get permission from land owners and never collect plants from federal lands.

Making the dye was easy. I boiled enough water to cover my yarn and poured that over the flowers. I used a wooden spoon to mash and stir the mixture and then let it sit overnight to extract the dye. The water turns a dark reddish brown. The next morning I strained the flowers and squeezed them to extract the most dye water as I could.

Most natural dye has a very earthy pallet, many golds, browns, olives, greys and soft mauves. Coreopsis tinctoria is known for light yellow to light brown, depending on the mordant used. We're using alum and cream of tartar for gold shades. For the skein of yarn that we'll be dyeing, I dissolved 4 tablespoons of alum and 4 tablespoons of cream of tartar in a gallon of water. This mordant bonds with the fibers and allows them to absorb more color. Bring that to a simmer and gently add your yarn to the pot after you've wetted it with hot tap water. Wool yarns must be treated gently during the whole process so they do not felt. Make sure the yarn is well saturated and gently push it under the water. Don't stir it, that toughens and felts the fibers. Put a lid on the pot and turn off the heat. You can either dye your yarn directly from the mordant bath, or drain it and let it dry for future use.

I brought the dye water to a simmer (about 175 degrees) while I strained the yarn from the warm mordant. It is important not to boil the yarn or shock it with an extreme temperature change. Add the yarn to the dye bath and let it simmer between 150 and 175 degrees for an hour. I gently poked and prodded the yarn to keep it under the dye. It probably wasn't necessary, but I was so curious about the process, I couldn't leave it alone. After an hour, I turned off the stove and covered the pot, letting this sit overnight and into the next afternoon. At that time, I removed the yarn, rinsed it in cool water and hung it to dry.

I brought the dye water to a simmer (about 175 degrees) while I strained the yarn from the warm mordant. It is important not to boil the yarn or shock it with an extreme temperature change. Add the yarn to the dye bath and let it simmer between 150 and 175 degrees for an hour. I gently poked and prodded the yarn to keep it under the dye. It probably wasn't necessary, but I was so curious about the process, I couldn't leave it alone. After an hour, I turned off the stove and covered the pot, letting this sit overnight and into the next afternoon. At that time, I removed the yarn, rinsed it in cool water and hung it to dry.

I now have a new appreciation for this labor intensive process and a new appreciation for all of those who worked so hard in the past to fill our lives with color. For more information about other dye plants and the recipes for each, I recommend these two books; Harvesting Color by Rebecca Burgess and A Dyer's Garden by Rita Buchanan.

Copyright © www.100flowers.win Botanic Garden All Rights Reserved