Everyone knows Lilacs, those lush shrubs with sprays of blossoms among heart-shaped leaves--a true heritage plant. With origins in Europe and Asia, Lilacs came to America with the first settlers in New England. In fact, Lilacs at the Governor Wentworth estate in New Hampshire are believed to have been planted around 1750. Hardy and forgiving, these deciduous ornamentals are often the only remaining hint that a field or city lot once supported a home or farm.

Sun-loving and low-maintenance, Common Lilacs (Syringa vulgaris) are perfect specimens for almost any garden. Once established in the proper setting, they need only light pruning and seasonal dead-heading to keep them looking beautiful year after year. Their heady fragrance fills the April air and stirs memories of grandmothers and childhood and love.

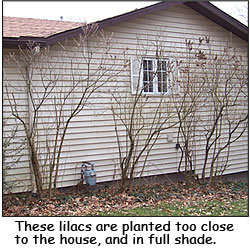

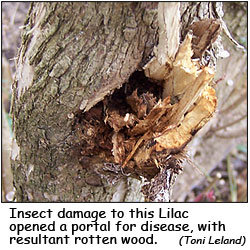

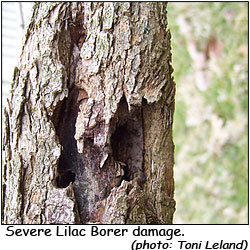

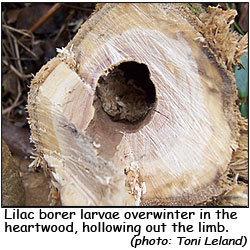

But tough as they are, if neglected for many years, Lilacs can become overgrown, diseased, and bloomless. When this happens, there is only so much you can do to rejuvenate them. When I moved into my current home two years ago, I stared with dismay at the overgrown, leggy, ugly Lilacs that had been planted 12 years ago along the northern side of the house. Why they’d been planted in the shade, I’ll never know, but since the species is strong, they’d struggled year after year to reach the sun. The result is 12 to 15 feet of bare limbs with topknots of leaves--and no flowers (see photo). Additionally, these shrubs had been planted only 2 feet from the foundation, and one sits directly in front of a dryer vent. (See my article on Planting for the Future.) On closer examination, I found evidence of infestation by Lilac Borer (Podosesia syringae) also known as Ash Borer, with resulting rotten wood.

with resulting rotten wood.

After much research, and a discussion with my local nurseryman, I had two options:

In either case, I would have no Lilac blooms in April, but in fact, I had none anyway.

I chose the second option.

Another Problem Spot

On the south side of the house, two Lilacs had been planted along the side of the garden shed. These bushes receive plenty of sun, but the drainage is poor and the area remains soggy. This past spring, I counted only 12 blossoms on one bush and no blossoms on the other. These shrubs had also been neglected over the years and, instead of

On the south side of the house, two Lilacs had been planted along the side of the garden shed. These bushes receive plenty of sun, but the drainage is poor and the area remains soggy. This past spring, I counted only 12 blossoms on one bush and no blossoms on the other. These shrubs had also been neglected over the years and, instead of

growing tall and gangly, they’d sent up masses of suckers, forming a thick central growing point that became a perfect spot for various tenacious weeds to establish themselves. A wild grapevine (Vitis riparia) rose from the center of the clump, sprouting each spring from a 3-inch thick vine that wrapped around the Lilac and climbed toward the sun. Several Virginia Creeper vines (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) also found a home in this spot, as well as a lone Poison Ivy vine (Toxicodendron radicans).

growing tall and gangly, they’d sent up masses of suckers, forming a thick central growing point that became a perfect spot for various tenacious weeds to establish themselves. A wild grapevine (Vitis riparia) rose from the center of the clump, sprouting each spring from a 3-inch thick vine that wrapped around the Lilac and climbed toward the sun. Several Virginia Creeper vines (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) also found a home in this spot, as well as a lone Poison Ivy vine (Toxicodendron radicans).

Same options as before: drastically prune, or remove.

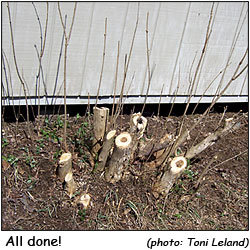

I chose to cut back and renew the largest shrub, and remove the smallest. In mid-March (Zone 6a), just before the buds began to swell, I bundled up for the 35-degree temperature, and trudged out with my pruning saw, loppers, and shears.

First, I raked all the debris from beneath the shrub, and hand-raked the years of accumulated stuff from between the trunks. Then I examined each large trunk for signs of Lilac Borer; all the limbs had been infested at some time.

Next, I identified the grapevine and Virginia Creeper and removed them close to the ground. Without being able to dig them out, I’ll need to cut them back regularly. I may try some spot applications of a weed killer directly on the cut. I’d need to wait on the Poison Ivy until it emerged later in the spring.

I then pruned away all the small lilac suckers, leaving only those measuring 3/4-inch or larger.

After identifying all the dead limbs, I removed those first.

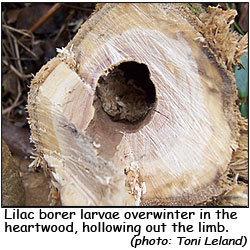

Then I cut the remaining trunks to about 2 feet. Some of these were hollow--borer larvae mature in the  heartwood over the winter. However, the wood was green and pruning would stimulate new growth.

heartwood over the winter. However, the wood was green and pruning would stimulate new growth. All this work resulted in some very bare areas in my yard, but with any luck, in a year or so I’ll again have the familiar scent of Lilacs drifting in my open windows.

All this work resulted in some very bare areas in my yard, but with any luck, in a year or so I’ll again have the familiar scent of Lilacs drifting in my open windows.

1 “Lilacs at Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University”: viewed 3/20/08 at http://www.arboretum.harvard.edu/plants/lilac_history.html

2 “Ash/Lilac Borer”: Utah State University Extension Fact Sheet No. 36, April 1993

3 “Lilac Borer”: National Science Foundation Center for Integrated Pest Management.

(Editor's Note: This article was originally published on March 31, 2008. Your comments are welcome, but please be aware that authors of previously published articles may not be able to respond to your questions.)

Copyright © www.100flowers.win Botanic Garden All Rights Reserved