Finish this as soon as possible as there is only just enough time left for the cultivated ground to be weathered sufficiently before the spring planting starts. Take advantage of hard frozen ground to wheel and place barrow-loads of organic matter, ready for mixing in when a thaw comes.

The addition of chalk to the soil of the ornamental garden is not as important as with the kitchen garden, but no plant likes extreme acid conditions; most of them will grow best in soils which have a pH of 6.0-6.5, ie. slightly acid. Some do better with a little alkalinity, of about 7.3-7.5. A test to discover the value of your soil is easily done and you can buy the materials for it in a kit, complete with instructions, from any good garden nursery.

A word about pH – it may sound mysterious and complicated, but as far as gardeners are concerned, all that it is, is a measure of how acid or alkaline the soil is. The reason for needing to know this is that, in very alkaline soils, some mineral nutrients – iron and magnesium are two – are present in a chemical form which makes it impossible for the roots of certain plants to absorb them. These plants are what is known as calcifuges and have to be grown in acid-reacting soils, if they are grown at all. The pH scale of acidity/alkalinity runs from 0-14; the lower figures show acidity, decreasing until they get to 7.0, which is the neutral point. After that increasing alkalinity is indicated up to the maximum of 14.0. In practice, most garden soils show a reaction somewhere between 5.0 and 7.5-8.0.

Besides altering the pH of the soil, lime has an effect on the soil structure, especially of heavy soils, and makes them easier to deal with and much less likely to be permanently saturated. Gypsum (calcium sulphate) is a particular form of lime which will break down such soils without altering the pH value, as it is neutral, and is particularly useful where the soil is heavy but already alkaline. Use a soil tester to find out whether this is the case in your garden.

There are various sorts of lime to use, the most common being chalk or ground limestone; both are calcium carbon- ate, ground limestone being slower in its action. Hydrated lime (calcium hydroxide) can also be applied; it acts more quickly. Rates of application will be given with the lime containers or with the soil-testing kit. Lime must always be put on with an interval of several weeks between its application and that of organic matter, to avoid a chemical reaction between them which results in the loss of plant foods.

Although it seems an unlikely time to supply food to plants, the spring-flowering bulbs – such as daffodils, scillas and crocus – will have poked through the soil by an inch or two.

They at least are active and, provided snow is not lying several inches deep, the ground is not hard with frost or sodden with moisture, they will appreciate a boost in the form of a general compound fertilizer at 90-120g per sq m (3-4oz per sq yd).

Plants are like other living organisms: they need food, not in solid form as with animals, but in the liquid state. The food they absorb from the soil consists of various mineral elements: phosphorus, potassium, sulphur and so on, each of which has a different function in the plant’s metabolism. In order that the plants can ‘eat’ them, these minerals must be broken up into minute particles which become part of the soil moisture and form a solution with it.

This solution passes into the plant roots, and from there to the other parts, the stem, the leaves and the flowers in particular, and the minerals then interact with the results of the process, known as photosynthesis, which goes on in the green tissue of plants.

Each mineral nutrient has a chemical symbol, for instance phosphorus is P, potassium K and nitrogen N. A packet of fertilizer will have the ‘analysis’ of the contents on it, that is, the mineral nutrients present and their percentage in the fertilizer will be shown: for example, Nitrogen, N, 7%, Phosphorus, P2O5, 4% and Potassium, K20, 9%. The phosphorus and potassium have to be present as compounds for technical reasons; in this analysis the potassium present is slightly more than the nitrogen, which would be good for flowering. More nitrogen would favour leaves and a higher proportion of phosphorus would encourage root growth. These three nutrients are the ones usually given as a supplement to organic matter, as they are the most important ones to plants, but others can be obtained and used if need be.

If plants do not have the mineral foods they need they show various symptoms of ill-health and will die if the deficiencies are acute or continue for long enough. However, the average garden soil, provided it is kept in good condition by the regular addition of rotted organic matter and an occasional application of proprietary fertilizers, should not lack the various minerals needed and discolorations of leaves are more likely to be the result of infections.

Mowing

It is unlikely that the next few weeks will be suitable for mowing, or even topping the grass, but occasionally a mild mid-winter occurs, when the birds sing, the sun shines and all sorts of plants show signs of growth, lulled into believing that spring has arrived. In such conditions, topping can be done, of established lawns, or those grown from autumn-laid turf, if it has put on some growth.

Watch the pool for a solid sheet of ice and remember that taking a hammer to it will sound like an explosion to the fish beneath; melt a hole in it if it is really thick.

Any late-flowering chrysanthemum cuttings taken in early winter should have rooted by mid-winter and will be ready for potting some time during this season. They can be transferred to individual 5 or 7.5cm (2 or 3in) diameter pots of J.I. No. 1 potting compost and, as a precaution, you can keep them in the propagating frame (but without extra warmth), or put plastic bags over each pot for two or three days, while they settle.

Early-flowering chrysanthemum crowns (stools) which have been overwintering in a cold frame may just be starting to produce new growth, so they can be encouraged by moderate watering near the end of mid-winter.

Sterilizing

Unless you are buying seed and potting composts made up ready for use, you will need to sterilize the loam for them early in mid-winter. It is then certain to be entirely free from the sterilizing agent when needed in late winter. A formalin solution is the most effective, the dilution rate with water being I part formalin in 49 parts water; 9L (2 gal) will treat 36L (1 bushel) of loam. The best method is to spread the loam out in a thin layer on a hard surface, water it well with the solution, mound it up into a heap and then cover to trap the fumes for 48 hours. After this it can be spread out thinly again and left to dry; allow three to four weeks at least for the fumes to evaporate entirely. Once the loam no longer smells of formalin, it is safe to use. Do not do the sterilizing in the greenhouse; formalin and its fumes are lethal to plant life. Peat and sand are already inert, and do not need sterilizing.

Continue to remove condensation from the inside of the greenhouse and leaves from the outside, to let in as much light as possible. You may have bonus light in the form of reflected light from snow. Keep the temperature as even as possible, not lower then 7°C (45°F) at night and 10-16°C (50-60°F) during the day, give a little ventilation during the day and shut down early in the afternoon, to retain as much of any sun warmth as possible. Water plants very carefully; give them just enough to wet the compost evenly all the way through and then leave them alone until the surface looks dry. At this time of the year, plants are touchy about their water needs: the amount should be exactly right.

You can continue to take cuttings from the cut-down late-autumn and early winter-flowering chrysanthemums until the end of mid-winter, and start with those produced by the early to mid-autumn-flowering kinds.

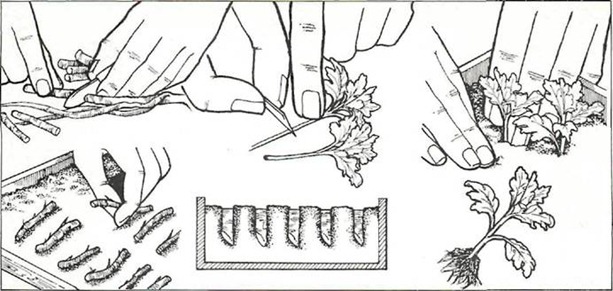

You can also use the roots of certain plants for cuttings; phlox, Oriental poppies and gaillardia are some. Phlox tend to suffer from a pest called stem and leaf eelworm, but if you increase the plants from root cuttings you avoid this trouble. Perfectly healthy plants can be produced from infested plants by this method of increase.

The roots are cut up into pieces about 2.5-5cm (1-2in) long; those from the poppies are put vertically into compost, the others laid horizontally on the surface and covered about 0.6cm (-Jin) deep. Kept in the gently heated greenhouse, they will root slowly, shoots will begin to appear and you can plant them out late in spring in their permanent positions after hardening off.

All the best seasonal gardening books insist that the well-organized gardener does his or her garden designing and selection of plants in the depth of winter, partly because it helps to supply text at a time of year when there is little work to discuss. Nevertheless, it has to be admitted that midwinter is a convenient time to take stock; for one thing, this is when the new seed catalogues are published, well in advance of the growing season. Since there actually is not very much to do outdoors and since spring, summer and autumn are times when you need running boots, the only peace you will have to consider and re-plan is the time when plant dormancy and hibernation have set in.

All the best seasonal gardening books insist that the well-organized gardener does his or her garden designing and selection of plants in the depth of winter, partly because it helps to supply text at a time of year when there is little work to discuss. Nevertheless, it has to be admitted that midwinter is a convenient time to take stock; for one thing, this is when the new seed catalogues are published, well in advance of the growing season. Since there actually is not very much to do outdoors and since spring, summer and autumn are times when you need running boots, the only peace you will have to consider and re-plan is the time when plant dormancy and hibernation have set in.

You could also make a resolution to keep a garden note-book. Details about times of sowing and planting, crop and flower yields, cultivations done, plant troubles, when pests and disease appeared and how you dealt with them, weed control and, above all, detailed daily notes about the weather, will all provide an extremely useful and entertaining garden work reference in future. Moreover, it will help to explain a good many otherwise inexplicable failures or successes, and to prevent the repetition of mistakes.

The length of time it takes for various seeds to germinate is an extremely useful piece of information which is hard to come by and a note about whether they germinate better in darkness or light is another.

Setting up a table to show the times of flowering of perennials, bulbs and so on, will show you where the gaps are in continuity of blooming. It is, incidentally, an eye-opener as to how useful various plants are. Some may be literally continuously in flower for eight weeks or more; others, very showy and popular, may last only two or three weeks and take up room for the remaining fifty weeks of the year without paying their way by having attractive foliage or growth habit.

An experimental gardener cannot do without a notebook if he or she has set up comparisons between various methods of cultivation or control of troubles, or hybridizing programmes, and the notebook can be made visually interesting with sketches, paintings or photographic prints.

All in all, the winter, if not physically active, can be mentally busy and suddenly, without any help from you, you will find the snowdrops are in flower, the aconites are shining in a corner and the time for sitting is past.

Copyright © www.100flowers.win Botanic Garden All Rights Reserved