For many people in the birding world, the joy of a bluebird may be unparalleled. From their magnificent plumage and melodic song to the uplifting thrill of their recovering population, no other bird inspires art, music or citizen-science participation quite like our native bluebirds. With a little help, the bluebird of happiness can be a part of your backyard too.

Photo by Steve PeckScientific and common names:

Photo by Steve PeckScientific and common names: There are three species of bluebirds in North America, all in the genus

Sialia:

eastern bluebird (

S. sialis), western bluebird (

S. mexicana), shown here on toyon (

Heteromeles arbutifolia), and mountain bluebird (

S. currucoides).

Philip Dunn

Male eastern bluebird

Keith Williams

Distribution: Clues to the distribution of bluebird species across North America can be found in their common names. The eastern bluebird resides east of the Rocky Mountains, from the Canadian border to the Gulf Coast, extending its summer range into Canada and venturing into Mexico during the winter. The western bluebird lives in the West, from high in the mountains down to sea level, wintering in the deserts and lowlands, and finding breeding grounds in more forested uplands, but rarely seen east of the Rocky Mountains.

In the West, from the Rockies to the Pacific Coast, the mountain bluebird, seen in this photo, can be found above 5,000 feet, wintering as far south as central Mexico and breeding in the summer as far north as Alaska.

This animated occurrence map, based on citizen-science reports through eBird, depicts the distribution of mountain bluebirds throughout the year.

Larry Keller

Habitat: A bluebird’s habitat, like that of most animals, must provide the resources the bird needs to eat, breed and be safe. Bluebirds nest in tree cavities. They eat a variety of ground-dwelling insects (beetles, ants, grasshoppers), switching to berries and seeds in the fall.

Ideal habitat for bluebirds includes open areas of short-growing grasses and sparse ground cover to forage for insects, scattered shrubs for perching while looking for food, and nearby trees or forest edges for breeding.

You’ll often find bluebirds in open country along field edges, perched on wires along roadsides, and in urban areas like golf courses and backyards. In this photo, an eastern bluebird sits in a cherry tree (

Prunus sp.).

When to look for them: In the Northeast, you can begin to look for eastern bluebirds in the early spring as they become more active, searching for nesting sites and feeding their young. Eastern bluebirds from the southeastern U.S. may be seen year-round, since some move only short distances south or can simply remain in their breeding territories all year.

Mountain and western bluebirds can be expected to be seen in the summer in rural areas, countrysides and ranches even at higher elevations. Some western bluebirds as far north as British Columbia, Canada, stay there year-round. Bluebirds living in mountainous areas simply move down the slope to warmer elevations for winter. Search for areas with berry-laden junipers, then watch for flocks of birds feeding on those berries.

Western and mountain bluebirds across the interior will depart their northern and western breeding grounds in September to winter in Arizona, western Texas and northern Mexico by October and November.

Photos by, from left, Vivek Tiwari, Anne Elliott and Megumi AitaHow to Identify Bluebirds

Photos by, from left, Vivek Tiwari, Anne Elliott and Megumi AitaHow to Identify BluebirdsBluebirds are thrushes, like American robins, and are about the same size. They have narrow notched bills suitable for pecking bugs from the ground or plucking berries from shrubs.

Plumage patterns differ slightly across the three varieties. All have a blue crown, nape, back, wings and tail. They also have a white underbelly and a white undertail. The biggest difference lies in the breast and throat colors. The

mountain bluebird (middle) has a blue breast and throat, while the

eastern and western bluebirds (right and left, respectively) have a red or chestnut breast, which extends up to the throat in the eastern bluebird.

A female, right, and a male eastern bluebird sit side by side. Photo by ptgbirdloverDistinguish between males and females.

A female, right, and a male eastern bluebird sit side by side. Photo by ptgbirdloverDistinguish between males and females. Bluebirds are sexually dichromatic, meaning that the sexes differ in their coloration. For many dichromatic birds, it is difficult to match the softer color tones of the female to their respective bright and showy males. Bluebird females, however, possess the same distinct markings and coloration as the males do, but they are subtle blue-gray and light red. Some people think that the light blue tinges on the wings and tail give the females a softer, more elegant appearance next to the bright, bold color of the males.

Photo by Yellowstone National Park

Photo by Yellowstone National Park

How to Attract BluebirdsCreate nesting habitat. Habitat for bluebirds has diminished greatly with changing land use and urbanization. This has especially reduced the available real estate for nesting sites — cavities in trees, often dead ones. Aggressive, invasive birds like European starlings and house sparrows quickly occupy or commandeer the few available sites, leaving bluebirds with reduced options for nesting.

The mountain bluebird pictured here is lucky to have found this unoccupied cavity in this tree snag. Allowing dead trees to stand in safe locations on your property and providing nest boxes for bluebirds are excellent ways to help create more nesting habitat for this beloved species.

Larry Imes

Plant berry-producing trees and shrubs. Plants like elderberry, sumac, dogwood, serviceberry and chokecherry provide a natural food source for bluebirds. These berries will persist into the winter and act as a food source when insects are scarce. This male western bluebird is stealing away with the last of these pin cherries (

Prunus pensylvanica) left from the previous year’s growing season.

6 Plants for Abundant Winter Berries

Photo by kansasphoto

Photo by kansasphoto

Welcome insects. In the spring, native plants attract insects to their blossoms, and host the caterpillars that will hatch from eggs laid the year before. An abundance of insects is critical to a successful nesting cycle for bluebirds, such as this male eastern bluebird, since they feed their young almost exclusively on this protein-rich food at this time of year.

Photo by C Watts

Photo by C WattsBluebirds are not readily found at bird feeders, but they will enjoy a pile of healthy mealworms if left out for them on a platform or in a bowl. This male eastern bluebird will probably fit a few more in his bill before flying off to feed the nestlings. Keeping low-growing vegetation and sparse ground cover in open areas near trees will give bluebirds places to find bugs on the ground as well.

Bob Vuxinic

Female, left, and male eastern bluebirds get their bills dirty digging into a seedy suet cake.

Fill feeders with protein. Bluebirds generally eat insects through the spring and summer, switching to fruit or seeds through the fall and winter, with the occasional insect mixed in when possible.

Interestingly, western bluebirds have been observed eating marine invertebrates on the beach, while eastern bluebirds have occasionally been observed feeding on shrews, salamanders, snakes, lizards and tree frogs. Their love of protein means they will readily visit suet offered in cages or blocks alongside your other backyard bird feeders.

Photo by John Benson

Photo by John Benson

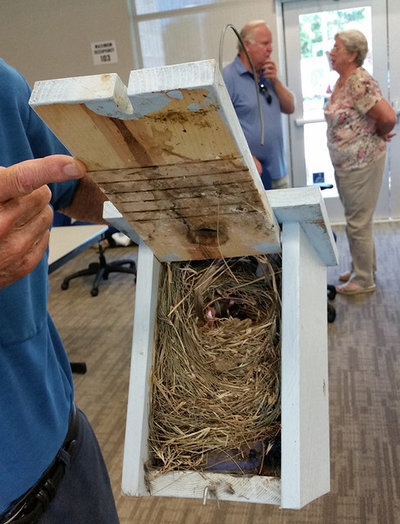

NestingAll three species of bluebirds are cavity nesters. They don’t, however, have the large bill or power to create cavities themselves, so they seek out nest sites in old woodpecker holes or other hollow spaces in dead tree snags.

Bluebirds are also adept at using nest boxes. In fact, the population has embarked on a remarkable recovery over the past couple of decades as a direct result of coordinated efforts by concerned individuals to build and appropriately place more nest boxes targeting bluebirds. This female eastern bluebird is gathering the necessary materials for her nest box. You can join this effort by downloading your own official Cornell nest box plans from Project NestWatch.

Eastern bluebird eggs nestle in a nest box. Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northeast Region

Eastern bluebird eggs nestle in a nest box. Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northeast RegionWestern bluebird pairs will seek out a nest site together, inspecting the cavities for suitability. The males of the mountain and eastern bluebirds select the sites and attempt to attract the female to it by carrying nesting material in and out of the cavity, perching on top and waving their wings.

After the site is selected, it is the female that does the building, including gathering the materials. The nest takes about a week to construct. It is made with straw or coarse grasses and pine needles; sometimes animal hair and mosses are added. The female bluebird lays two to eight eggs and incubates them for an average of two weeks.

Mike Bons

Two eastern bluebird fledglings learn the ropes.After about three weeks, the young are ready to fledge. They will stay with the parents for a short while, spending less and less time at the nest until they eventually do not return.

The parents tend to stay together through the winter and breed again the following year, often in the same place. Western bluebirds, however, are a cooperative breeding species. They stay together as families and communities through the winter, sometimes piling up to 15 birds in a cavity for warmth and protection. After initially fledging, the daughters will leave and the sons will stay in the flock, joined by daughters from far away and unmated males from nearby.

Dave Biddle

When breeding season returns, and the time to select cavities for nests is in full swing, things can heat up as birds compete over the limited choices of prime sites. The western bluebird in this photo is defending its territory against the mountain bluebird’s attempt to steal a site. Males of the same species will also square off over nesting cavities, often engaging in fast-paced chases and pinning each other to the ground.

Photo by David SalahiProtecting bluebird nests.

Photo by David SalahiProtecting bluebird nests. Confrontations with house sparrows over a territory can be deadly for the bluebird, especially if they take place inside the nest box. In this photo, a house sparrow has made a nest on top of the defeated bluebird.

Many people actively provide, monitor and protect nest boxes to help defend native bluebirds from invasive species like house sparrows and European starlings. There is a new citizen-science effort examining this competition to develop ways to help bluebird conservation. You can also trade in any house sparrow eggs from nests you find for fake replacement eggs to put back in the nest, which will keep the sparrows from attempting a new nest. Visit the project website or Facebook page to learn more and begin attracting and protecting beautiful bluebirds in your backyard this spring.

See more ways to welcome birds to your garden

YardMap is a citizen science project developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, designed to cultivate a richer understanding of bird habitat, for both professional scientists and people concerned with their local environment. Thousands of people are documenting their conservation efforts at home to support birds and other wildlife in their yards.