A bright red flash in a frosty white woods. The quiet of this soft, snowy morning is cheerfully pierced with the clear, vibrant whistle of a northern cardinal. The unmistakable song of this colorful year-round resident will insistently announce the day from late winter through spring and into early summer. Cardinals are nonmigratory birds that don’t molt into dull winter plumage, allowing their crimson brilliance to shine all year long as far north as southern Canada.

More Backyard Birds: American Goldfinches | American Kestrels | Chickadees | Hummingbirds | Jays | Northern Flickers | Nuthatches | Owls | Warblers | Woodpeckers

Larry Belt

eBird

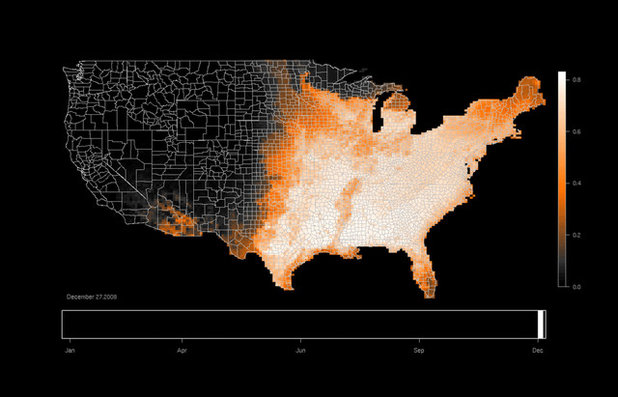

Check out this occurrence map from eBird and watch the yearly range adjustments, then continue on to learn more about the behavior of cardinals and how you can invite them, and a few other red birds, to your yard this year.

Rockytopk9

Family: Cardinalidae, which also includes grosbeaks and buntings

Latin name: Cardinalis cardinalisCommon name: Northern cardinal

Distribution: Abundant throughout the eastern United States, northern cardinals can be found from Maine to Florida and west to Minnesota, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. Some southern populations extend across lower New Mexico into central Arizona. They’ve also been introduced in Hawaii and can be found on the main islands.

Habitat:

Habitat: Northern cardinals are a superb generalist species and inhabit a wide range of environments, from remote forests to dense residential areas. You’ll likely see them almost anywhere throughout their range, from backyard bird feeders, suburban gardens and local parks to woodland and marsh edges, thickets, shrubby grasslands, successional meadows, and hedgerows in agricultural fields.

When to look for them: Year-round

Photo by Rodney Campbell

mrecount

How to Identify Northern CardinalsBesides its colorful plumage, the northern cardinal can be recognized by its very large and orange conical bill surrounded by a solid black face mask. It has a tall crest on the top of its head that it can raise or lower for display or communication and a long, straight tail. About as big as a robin, this large songbird is one of the easier backyard birds to spot and positively identify.

Lindapp57

Juvenile northern cardinals have the crest, but they’re brown with a gray to black bill that changes to orange as they reach adulthood. They’ll complete their molt into full adult plumage within a couple of weeks after fledging the nest. The bird shown here is a young cardinal midway on the journey to adult coloration. Notice the coloration on the beak (both orange and black), and the beginnings of red adult feathers on the wings and tail.

Steve Shelasky

Differences between males and females. The male northern cardinal is well-known for his intense and striking red plumage. From the tip of the tail to the top of the crest, he proudly wears these colors year-round. Northern cardinals don’t molt into a dull plumage in the winter like most male songbirds.

The female is mostly tan and brown, with warm tones of red splashed on the wings and tail, and decorating the tip of the crest. Her black mask isn’t as large or pronounced as his, but she still sports that bright orange bill. Even with the absence of the bright red plumage, the female is a striking, colorful bird and occasionally elicits reports to the Cornell Lab of a mistaken “exotic” species visiting a backyard feeder.

Matthew Addicks

How to Attract Northern CardinalsHang bird feeders. Primarily seed eaters in winter, northern cardinals dine on the fruits and nuts of trees, shrubs, grasses and weeds. Nearly any bird feeder will be able to provide a seed source they’re happy with, but, like many feeder birds, they prefer black-oil sunflower seeds. They’re likely to take the morsel to a nearby bush for cover and then return, repeatedly, for another.

In the spring and summer, northern cardinals bound among branches and blossoms, looking for bugs like beetles, butterflies and their larvae. The female cardinal shown here may be able to collect a six-legged meal among the flowers of this eastern native mountain laurel (

Kalmia latifolia).

Dan Behm

Plant native trees, shrubs and flowers. With a bill highly adapted for removing seeds from shells, the northern cardinal has a diet consisting of 71 percent plant material, and 29 percent insects and larvae. The seeds, fruit and insects on which the bird depends are found in abundance on native trees, shrubs and flowers.

Incorporate plantings of native shrubs like dogwood (

Cornus spp.) and elderberry (

Sambucus spp.), native vines like wild grape (

Vitis spp.) and blackberry (

Rubus spp.), and native sedges (

Carex spp.) or grasses to attract these birds to your garden. Trees that provide resources for northern cardinals are mulberry (

Morus spp.), hackberry (

Celtis spp.) and tulip tree (

Liriodendron tulipifera), among others.

The male cardinal shown here is likely grateful for the fruits still present on this crab apple branch late into the winter.

Jonathan Fredin

NestingNest building for the northern cardinal begins in late February — sometimes while there’s still a bit of snow on the ground — and extends to mid-April. The male and female both scout for locations, carrying a bit of nesting material around with them as they check various sites. They will call back and forth while looking for a suitable location, trying out the material in the fork of a branch here and there, then moving on.

Nests are typically built low in a dense thicket, shrubbery or tangle of grapevines. The birds will use many kinds of trees and shrubs, including dogwood, honeysuckle, spruce, pine, hemlock and maple.

After the two agree on a location, the female will spend the next week (or possibly two, depending on conditions and resources) building the nest from sticks, leaves and grapevine bark, then lining it with soft insulating materials like grasses, plant stems, rootlets and pine needles. She will crush the larger twigs with her bill to soften and make them more flexible, pushing them out with her feet while turning in circles to place the pieces.

During construction, the male will bring food for the female while she tirelessly creates a bowl-shaped cup nest wedged in place between forked branches.

Photo by Steven Depolo

Josh Jones

Nests contain two to five eggs and require almost two weeks of incubation. Only the female will brood the eggs in the nest, but the male will bring her food and occasionally stand guard while she’s briefly away. When the nestlings hatch, they’re altricial, blind and helpless, like most songbirds.

Both the male and female will feed the young a diet of mostly insects. Feeding can be as often as four times an hour for the first two weeks, depending on clutch size. The parents need a lot of bugs close by to raise a healthy brood. A native and diverse habitat can provide the plentiful selection of insects a young cardinal family needs.

Young will leave the nest just nine to 13 days after hatching. They’ll be strong fliers after a week and fully independent of parental care one to two months after fledging.

Kelly Colgan Azar

Unique Northern Cardinal TraitsThe northern cardinal is one of the few North American songbirds where the female also sings, often while sitting on her nest. A mated pair can share phrases of a song, but the female may even sing a longer and more complex song than the male.

Listen on cold mornings for this treetop duet or check out this YouTube video to see (and hear) a pair of cardinals carrying on.

Jeff Clow

The male northern cardinal can be obsessed with defending his breeding territory from other males, most often in spring and early summer when trying to attract a female. Attacks with bill and claw are either in the air or on the ground. He may just posture with stern gaze and lowered crest in a formidable display or give continual chase for up to 30 minutes. In the spring, he may even attack his own reflection in a window, car mirror or shiny bumper. Male cardinals have been observed spending hours fighting these imaginary intruders without giving up.

Judith Gandy

Certainly one of the more popular birds in North America, the northern cardinal is the state bird of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia. Two professional sports teams and several universities have made the cardinal their mascot. With its bold colors and fierce territorial nature, it’s not hard to see why.

Stuart Oikawa

Other Red Birds to KnowIf you don’t live in the range of the northern cardinal, there are a couple of other magnificently red birds you may be able to attract to your backyard using native plants, healthy habitat practices and, of course, feeders full of plentiful seed.

Pine grosbeak. The pine grosbeak, shown here, resides in the northern boreal forests of Canada in the summer but will often occur farther south in the winter, from Wyoming and the Dakotas to the mountain ranges of Utah, Idaho and California, and across certain parts of the Northwest.

See the range map for the pine grosbeak

The pine grosbeak is one of the largest finches, with a puffed-out chest, large rounded head and big stubby bill (check out how it towers above the common redpoll in the previous image). The male is red with brown wings and two white wing bars. The female is similar but lacks the red pigment.

Pine grosbeaks eat primarily fruits and seeds, and, as a flock, are known to strip a plentiful tree of fruits before moving on to the next. They prefer seeds from spruce, pine and juniper, as well as elm, maple and mountain ash. Adult pine grosbeaks rarely feed on insects or spiders but will feed them to their young, often mixed with plant material.

Attract them to your yard with feeders, and native evergreen trees for food and nesting resources.

Photo by David A Mitchell

Terry & Joanne Johnson

Red crossbill. Found throughout Canada, in the Rocky Mountains and along the western coast of North America, red crossbills almost exclusively inhabit evergreen forests.

Unique to the bird world, crossbills have a powerful adaptation to their bills to facilitate seed removal from conifer cones. Looking at the tip of their bill, you’ll notice that the top part goes one way, and the bottom goes the other, giving them the crossbill name. The bill is used pry up a scale on a conifer cone to expose the seed.

Terry & Joanne Johnson

The female crossbill, shown here, is olive-gray with a greenish-yellow rump and chest, brown wings, and a crossed bill, like the male.

This efficient bill adaptation, however, makes crossbills dependent on conifers as a food source, even to the point of feeding their young the same seed at birth. As a result, red crossbills breed at various times throughout the year, whenever an abundant seed source is located.

You can invite them to your backyard by planting native conifer trees like spruce, pine and Douglas fir. If the food source is significant enough, you may even find a nest hidden among the spruce branches.

Summer tanager.

Summer tanager. Another very red bird — the only completely red one in North America — is the strawberry-colored male summer tanager. It’s an eye-catching sight against the green leaves of the forest canopy.

The mustard-yellow female is harder to spot, though both sexes have a distinctive chuckling call note.

Fairly common during the summer across the southern U.S., these birds migrate as far as the middle of South America each winter. All year long, they specialize in catching bees and wasps on the wing, somehow avoiding being stung.

YardMap is a citizen science project developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, designed to cultivate a richer understanding of bird habitat, for both professional scientists and people concerned with their local environment. Thousands of people are documenting their conservation efforts at home to support birds and other wildlife in their yards.Photo by Mitchell McConnell

See more ways to welcome birds to your garden