Agave have a long history of being used as an accent plant in the landscape, where they attract attention wherever they are planted. With their succulent leaves reaching up toward the sky, agaves add a great spiky texture to the landscape. The ability of agaves to thrive in drought-tolerant landscapes in sun, shade and even in containers makes them extremely versatile and suitable for growing in every climate zone.

Native to the Americas, agaves are often referred to as century plant. This is due to the fact that most agaves bloom once in a lifetime, producing a fast-growing flowering stalk, after which they die and leave behind seed or offsets to take their place in the landscape. There are more than 200 recognized species of agave, with an almost endless variety of color, size and leaf shape. From plants less than 12 inches wide to some more than 10 feet across, there is an agave for almost every landscape.

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Where Agave GrowsAgaves can be found naturally growing at sea level to mountains 7,000 feet in elevation. Their natural habitat ranges from the U.S. Southwest through Mexico and into Central America and northern areas of South America. The vast majority of agave species are found growing in Mexico, while the southwestern United States has the second-largest number of species. Agave’s native range is not limited to arid regions; there are also species native to the Caribbean and Florida.

Shown: Whale’s tongue agave

(

Agave ovatifolia) growing in filtered shade alongside the succulent ground cover elephant bush (

Portulacaria afra)

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Desert grasslands, particularly in the mid- and high-desert regions, are home to many species. Agave can also be found growing on rocky hillsides, forests and even in coastal environments.

The majority of agave species can grow outdoors in zones 8 and above, but some can be grown in colder climates, such as

A. parryi var.

neomexicana, which can handle the -20 degree winters of USDA zone 5 (find your zone).

Shown: Black spined agave

(

A. macroacantha)

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Distinguishing TraitsWhile the color, shape and size of agave leaves can vary, they all grow in a rosette shape around a stem that is invisible in many species. It is this rosette pattern of growth that makes agave attractive to so many.

The color of agaves ranges from deep green to gray-blue. Leaves are covered in a waxy cuticle that helps reduce water loss.

Shown: Artichoke agave

(

A. parryi var.

truncata)

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Agave leaves vary widely in their shape. Some are very narrow, such as those of twin-flowered agave (

A. geminiflora). Other species have long, thick leaves, like those found on octopus agave (

A. vilmoriniana) or smooth edge agave (

A. desmettiana).

An imprint of the surrounding leaves is a decorative detail found on the leaves of several agave species. The imprint happens when the leaves are formed in the bud, where they are held tightly inside for two to three years before emerging.

Shown: Leaf imprints on mezcal ceniza (

A. colorata)

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

At the tip of each agave leaf is a terminal spine that can hurt you if you get too close. The tips are often an ornamental feature of the plant and are sometimes a different color than the leaves themselves. You can easily clip the spines off.

Agave leaves are often toothed along the edges (the teeth vary in size and length), although some species have smooth edges or long filaments.

Shown: The terminal spines of smooth edge agave

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Some agave species have as few as 20 leaves, while others can have more than 200. The leaves are fibrous and can live a long time — some last the lifetime of the plant. Some people prefer to prune the leaves off as they age, but it is not necessary to the health of the plant.

Shown: Queen Victoria agave (

A. victoria-reginae)

The Plant Man Nursery

Agaves store water in their fleshy leaves, enabling them to survive periods of drought. In addition, their rosette shape channels water toward the base of the plant, where their roots are located. Their roots shrink during periods of extended drought, which creates a small crack between the base of the agave and the surrounding soil and allows the collection of more water once rainfall arrives.

Shown: Artichoke agave planted in front of milk bush (

Euphorbia tirucalli ‘Sticks on Fire’)

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

How Agaves ReproduceAgaves reproduce in several ways, one of which involves the production of offsets, or “pups.” A number of agave species produce an underground rhizome, which produces young agave plants that appear close to the parent plant. These offsets will continue to survive even after the parent plant dies.

The offsets can be allowed to grow where they are or removed from the mother plant by severing the underground root (rhizome) and replanted elsewhere. Some agave species, such as American century plant (

A. americana)

and smooth edge agave, produce a lot of offsets, while others, such as Queen Victoria agave, produce few to no offsets.

Shown: A hummingbird perched on the tip of one of the leaves of an American century plant with numerous offsets

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Agaves also reproduce through flowering. Agaves are monocarpic, which means that they flower once in their lifetime. The process of sending up a flowering stalk, which produces flowers and later seed, marks the crowning achievement of an agave’s life, after which the agave will die.

The big question most people have is how long it will take an agave to flower. The answer is largely dependent on the species — some live 10 years before flowering, while others can survive 50 years or more. Smooth edge agave and octopus agave can flower as early as seven years after planting, whereas other species, such as Queen Victoria agave

, can wait 20 to 30 years before flowering. Agave grown in humid climates, like that of the Southeast, or that receive supplemental water, will flower earlier than those grown in naturally dry climates.

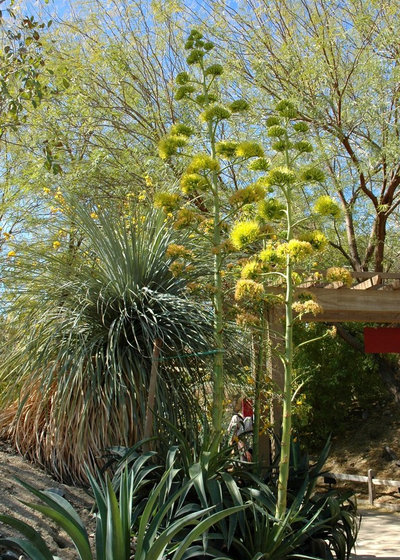

Shown: Flowering smooth edge agave at the Living Desert Museum in Palm Desert, California

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

When it gets ready to flower, agave sends up a thick stalk that grows up to 1 foot a day. The flowering stalk can be as short as 5 feet and grow up to 40 feet tall. The flowering stalk’s height is dependent on the species. The rapid growth of the stalk and later the formation of flowers is truly a remarkable display of nature, and you would be lucky to witness it.

Shown: An agave just beginning to send up its flower stalk

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Agave StalksThere are two different types of agave stalks. The most popular form is called a panicle and forms the characteristic agave flower with arms reaching out from the center stalk. Flowers form at the ends of the arms and are pollinated by bats, bees, hummingbirds and other insects. As the flowers fade, seed is produced and sometimes small agave bulbils also form, which can be planted.

Shown: Weber’s agave (

A. weberi) sending up a panicle flowering stalk

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Another type of agave stalk is called a spike; flowers form directly on the main stalk.

Shown: Octopus agave

with the less common spike flowering stalk

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Small bulbils form on the stalk of certain agave species, such as this octopus agave

, which can be planted in the ground or in containers.

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Some people cut off the stalk before it flowers, thinking that they will prevent the agave’s death. Not only will doing that fail to keep the agave alive, but it will also rob you of seeing a magnificent feat of nature. After the flowers have faded and the agave has died, the flowering stalk is often used in home decor, where it is highly prized by many designers.

Pat Brodie Landscape Design

How to Use ItAgaves are extremely versatile in the landscape. Large species, such as variegated century plant (

A. americana var.

marginata) and Weber’s agave draw your attention with their thick, fleshy leaves, adding both color and texture to large landscapes.

While agave looks great when planted alone or in rows, it can also be paired with ground covers such as blackfoot daisy, damianita, trailing lantana (

Lantana montevidensis) or verbena

(

Glandularia spp) to show off the textural contrast of softly mounded forms alongside spikes.

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Popular small agave species, such as black spined agave, Ocahui agave (

A. ocahui),

A. schidigera and

Compacta Queen Victoria agave (

A. victoria-reginae ‘Compacta’), make great container plants or borders. Plant them close to paths or in groups of three to five so they can be seen.

Medium-size agave often used in the landscape include cow’s horn (

A. bovicornuta), smooth edge agave and whale’s tongue agave,

just to name a few. These midsize agave can also be used in containers or placed alongside boulders in the landscape. Those without teeth at the edges are especially suitable for landscaping around swimming pools.

Shown: A. schidigera, a small agave with smooth edges and long, white filaments

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Contemporary landscapes are great places for agave, whether planted singly or in rows. Other succulents, such as golden barrel cactus (

Echinocactus grusonii) and prickly pear (

Opuntia santa-rita),

also look great when paired with agave.

Shown: A young American century plant alongside golden barrel cactus and aloe in a contemporary landscape design in Scottsdale, Arizona

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Agave in containers. Smaller agave species make great container plants, which is especially helpful for the person who wants containers filled with fuss-free plants. Sun-loving agave, like mezcal ceniza, Ocahui agave, artichoke agave and Queen Victoria agave will do well in areas with hot, reflected sun and limited water.

As with most succulents grown in containers, agaves need to be fertilized. In low-desert regions with hot summers, agaves actively grow in spring and fall, which is when they should be fertilized. In cooler climates, fertilize them in late spring through the summer. Apply fertilizer once a month during the active growing season to the surrounding soil using an all-purpose liquid fertilizer (10-10-10) diluted to half strength.

Though agaves are not fussy, they must have well-drained soil. When planting agaves in containers, be sure to use a planting mix specially formulated for succulents that is fast draining.

Shown: Artichoke agave grown in containers with elephant’s food in the background

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Growing agave indoors. Don’t despair if you don’t live in a warm region where agave can be grown outdoors all year round. Because agaves do so well in containers, they can be grown outdoors throughout most of the year and then brought inside and placed by a sunny window all winter long. If you don’t have an outdoor space in which to place your container agave, simply grow it indoors all year long.

When growing agave indoors in containers, place it by a west- or south-facing window. Agaves grown indoors will need more water than those planted in the ground and should be watered when the soil is dry.

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Planting NotesAgaves prefer rocky or sandy soil but will do well in any well-drained soil. Research the species of agave to see whether it grows well in full sun or if it needs filtered shade or afternoon shade to do its best. If in doubt, plant in light, filtered shade.

Water once a week in summer, when temperatures are above 100 degrees, to a depth of at least 1 foot. In spring and fall, water every two to three weeks. In the winter agaves can usually survive on rainfall alone, since they do not actively grow then.

Shown: A. franzosinii

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

While many agave species thrive in full sun, such as Parry’s agave, Queen Victoria agave and Weber’s agave, some do best in filtered shade, particularly in the low desert. Agave species such as smooth edge, twin-flowered, whale’s tongue and octopus agave welcome the light shade provided by mesquite (

Prosopis spp) or blue palo verde (

Parkinsonia spp). If filtered shade is not available, shade cloth can be used to cover the affected agave.

Shown: Agave protected from the summer sun with shade cloth at the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Agaves of the same species can look different depending on the climate they are grown in. An American century plant, for example, grown in South Carolina, will grow much larger than one grown in Arizona, due to increased humidity and rainfall. As a result of the extra water availability, the one shown here in South Carolina will likely flower sooner than it would have in a drier setting.

Shown: The writer standing by a very large agave growing on the University of South Carolina campus

Noelle Johnson Landscape Consulting

Large agaves are expensive and won’t last very long in the landscape before they flower. Look for agaves grown in 1-, 3- or 5-gallon pots. Sometimes you can even find more than one agave growing in a single nursery pot, thereby getting more for your money.

Shown: Large boxed artichoke agaves