When you walk into a garden center or nursery, you’re almost always going to see one kind of coneflower:

Echinacea purpurea. Oh, you’ll see lots of different coneflowers, often the hottest new thing to tempt you, but they are pretty much always a cultivar of

Echinacea purpurea. They’ve been selected to be shorter, to have a different color or to have weird flower heads that are all petals, like some sort of deformed pompom. Two caveats about these cultivars: 1. Some of them tend to be weaker than the straight species and 2. If there are only petals, where are the insects going to get nectar? And what will the birds eat come winter if no seeds form from pollination?

I propose a succession of native species coneflowers that have not been bred, crossed or altered in any way — in other words, you could theoretically walk out into the wild and find them. One admission: Not all of these coneflowers will be native to where you are. While I am a big promoter of using local plants, I also think the following will provide a bit more insect benefit and be stronger if you are a coneflower-aholic (that’s a technical term, trust me).

Benjamin Vogt / Monarch Gardens

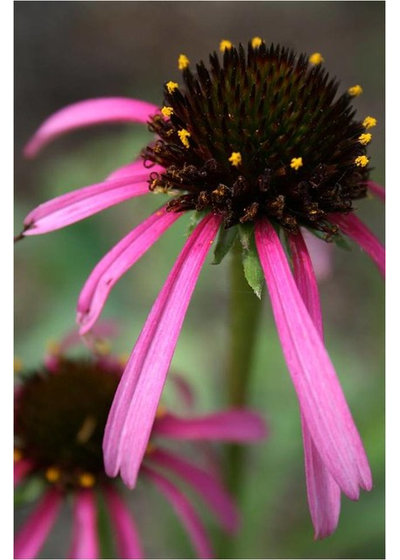

Yellow Pollen Coneflower (

Echinacea simulata)

Native to select parts of the U.S Southeast and MidwestAll coneflowers have pollen, but few have pollen as ornamental as

simulata’s. It’s the first echinacea to bloom for me, sometimes in late May here in eastern Nebraska. It’s native to a relatively small area — southeast Missouri and north-central Arkansas, with scattered holdouts in Kentucky and Tennessee. As with most other coneflowers, it likes medium to dry soil in full sun, and gets about 2 to 3 feet tall.

Also check out the rare

Reflexed Coneflower (

Echinacea atrorubens). It has very short petals and is native to a thin strip from the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas south through Oklahoma into Texas; it blooms in June.

Missouri Botanical Garden

Yellow Coneflower (

Echinacea paradoxa)

Native to the Ozark region in Missouri and ArkansasThe paradox here is that it’s yellow. Blooming in June, it puts on a good, long show even as the petals fade. It also has a small range due to habitat loss.

Paradoxa is often bred with

E. purpurea to make those crazy hybrids.

Missouri Botanical Garden

Pale Purple Coneflower (

Echinacea pallida) Native from Louisiana through Illinois and southern Wisconsin, west to Kansas and OklahomaThis is probably one of my favorites, because the petals get long and dangly and are quite pale, while the leaves and stems are particularly fuzzy. Pale Purple blooms from June to July and has a decent growing range.

Barbara Pintozzi

Purple Coneflower (

Echinacea purpurea)

Native to most of the eastern half of the U.S., more sparse toward the East CoastI don’t have to say much about this July-to-August bloomer, do I? It’s a lovely plant that’s used very often, and of course all coneflowers look stunning in winter — particularly with snow carefully stacked atop their seed heads.

Blooming about the same time is the

Black Sampson or

Narrow Leaf coneflower (

Echinacea angustifolia). Native to a large area from the southern to the northern Great Plains, it is sort of a mix of almost all of the coneflowers — except for

paradoxa and the next one.

Missouri Botanical Garden

Tennessee Coneflower (

Echinacea tennesseensis)

Native to TennesseeRecently taken off the endangered species list, this late-summer bloomer is native to a small area in central … wait for it … Tennessee. It’s a bit shorter at 2 feet tall, but it’s a coneflower worth preserving.

Benjamin Vogt / Monarch Gardens

So there you go — a bunch of coneflowers I bet you’ve never heard of but that are darn neat and will give you blooms all summer long. There’s more than

E. purpurea and its cultivars out there, and if you can appreciate the subtle simplicity of the many species coneflowers, you’ll come to see echinacea in a whole new light. I sure have.