I've been gardening and writing about gardening for more than 20 years, yet I find I'm always learning new things about the plants, insects and other critters that call my backyard home. That's the great thing about gardening — it's never boring! I've worked as a landscaper, on an organic farm, as a research technician in a plant pathology lab and ran a small cut-flower business, all of which inform my garden writing. A few years ago my husband and I purchased a beautiful old Victorian house and opened a pet-friendly B&B; I've spent the last few summers renovating garden beds and adding new ones. My husband once asked me when I'll be finished, to which I replied, "Never!" For me, gardening is a process, not a goal.

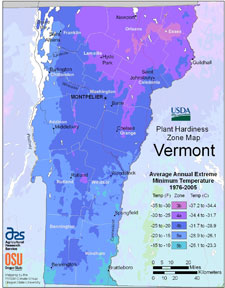

On its web site, the USDA offers click-and-zoom maps and single-state maps, so you can really zoom in on your zone. If you don't know your zone, you can find it by zip code. Explore at planthardiness.ars.usda.gov

Will that pretty perennial or berry bush grow in my backyard? There's a new way to help find the answer. On the USDA's 2012 version of the U.S. Hardiness Zone Map, colorful stripes delineate the zones in 5-degree Fahrenheit increments, from zone 1a (-60 to -55F, found only in Alaska) to zone 13b (65 to 70F, found only in Puerto Rico) and everything in between.

Although you won't find palm trees growing in Maine any time soon, many gardeners are finding themselves in a half-zone warmer region on the new map — 8b instead of 8a, or 6a instead of 5b, for example. (A relative few will find themselves in a cooler zone.) The creators of the map say the warming trend is due to more sophisticated measuring equipment, a longer period from which the averages were drawn, and additional weather monitoring stations. Nobody is mentioning climate change, so I won't, either.

Even though I'm still in zone 4b, with an average minimum temperature of -20 to -25F, I've experienced winters where it's dropped into the minus 30s. That's a good reminder that this map represents the average coldest temperature, not the record coldest. That means that in half the years the temperature drops below the average minimum, and in half it doesn't.

Most gardeners are familiar with the hardiness zones. They're found everywhere, from seed packets and nursery tags to reference books and websites, and slowly they'll all be switching over to the new map. Hardiness ratings are handy guidelines that can help you select perennials plants, trees and shrubs. If you live in zone 5, you can be relatively confident that a plant rated hardy in zones 1 through 5 will tolerate your winter temperatures.

Gardeners may be tempted to rush out and buy plants for their newly designated zone. However, despite the hullabaloo about the new map, it does have limitations, because many factors besides cold hardiness affect a plant's ability to thrive.

The Himalayan blue poppy (Meconopsis baileyi, previously M. betonicifolia)

As a new gardener flipping through plant catalogs, I immediately fell in love with Himalayan blue poppy, (Meconopsis baileyi, previously M. betonicifolia). With flowers the color of the prettiest summer sky, I was smitten. However, with a hardiness rating of USDA Zones 7 to 8, there's no way the plant would survive here in northern Vermont. So imagine my surprise when I took a trip even further north, to Jardins de Métis (aka Reford Gardens) in Quebec, and saw thousands of blooming blue poppies. Surely I wasn't in a zone 7 microclimate this far north.

This story illustrates the limitations of the hardiness zone map. Why does the Himalayan blue poppy flourish in chilly Quebec, a hundred miles north of the northern tip of Maine? Because the conditions at near-sea-level Reford Gardens mimic those of the plant's native habitat in the 10,000' mountains of Tibet: cool, moist summers and reliable winter snow cover that insulates roots and moderates the soil temperatures.

In the U.S., zones 7 and 8 include places as diverse as Raleigh, North Carolina; San Antonio, Texas; Las Vegas, Nevada; and Seattle, Washington. Of the four cities, only gardeners in Seattle, with their cool, moist summers, have a prayer of growing Himalayan blue poppy, which would succumb in the other cities' blistering summer heat.

Many factors besides minimum winter temperature affect a plant's ability to survive. In places with hot summers, heat tolerance is as much or more of a consideration when choosing plants. That's why the American Horticultural Society developed the Heat Zone Map.

Other factors include the duration of cold temperatures, alternating freezes and thaws, seasonal rainfall patterns, sunlight intensity and humidity. Soils play an important role, too, including the type, pH, organic matter and moisture levels.

Although the new hardiness zone map is a useful tool, don't rely on it too much when selecting plants for your landscape. Consider each potential plant's native habitat. A perennial that is adapted to sunny desert conditions will have a tough time in a cloudy, wet climate, even if it's the right hardiness zone.

If you're new to gardening, ask a gardening neighbor, consult with local garden centers and scan plant lists at public gardens. Occasionally, you might be surprised to find plants rated a zone or two warmer thriving in a sheltered spot or covered with protective mulch every winter by a diligent gardener. If you're willing to take extra steps to protect marginally hardy plants, by all means give them a try. But be realistic and focus on plants that are likely to thrive without extreme measures.

Region-specific online resources and magazines abound. Choosing plants that are adapted to your region goes a long way in creating a beautiful and low-maintenance landscape. Go ahead and take chances with a few less-than-ideal plants you fall in love with, but know the risks.

Some day I'll try growing Himalayan blue poppies here in Vermont. We usually get plenty of snow over the course of a winter, and our summers are relatively cool. But most years we get at least one midwinter thaw that melts the snow down to bare ground, followed by a deep freeze that would likely kill the plants' roots. The fact that I've never seen this beautiful plant growing near here, nor have I heard of any neighboring gardeners' success stories, tells me that even if it survives a year or two, the Himalayan blue poppy is unlikely to thrive. For now, I'll settle for enjoying the photos from my trip to Quebec.

Copyright © www.100flowers.win Botanic Garden All Rights Reserved