Grading is the process of shaping and contouring the land and is an important technical tool of landscape architects. Grading is important because the shape of the ground makes water flow across it in a particular way, and elegant grading creates a solid framework for the landscape’s design. Grading plans are necessary for an overall drainage plan that works with the entire property and melds with the existing context. Here is a primer on how grading interacts with the landscape design on a large scale and what specific grading techniques can be used to shape the ground on a more detailed level.

Falon Land Studio LLC

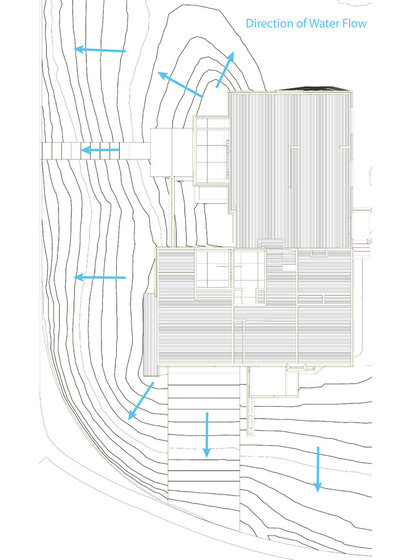

Grading BasicsGrading plans are tough to interpret when you do not have much experience reading contour lines, which are used to express topography. This basic diagram shows how water flows across the existing contour lines. The squiggly lines are the contour lines, and the arrows show water flow.

The contour lines are drawn in 1-foot increments, which represent the grade change on the site. The contour lines that are close together show a steep slope; contours spread farther apart represent a more gradual slope. The evenly spaced lines across the driveway and walkway leading to the door represent a consistent slope across the length of paved surfaces.

Landscape architects and civil engineers are the two types of professionals who are licensed to create grading plans. The requirements for using each type of professional vary by municipality. Often a licensed landscape architect or licensed professional engineer is required to design and stamp an overall grading plan as part of a building permit application. Check the requirements with your building and inspection department to determine if you need a licensed landscape architect or a licensed professional engineer. In some areas it comes down to how much soil is being moved. For major earthworks the grading usually needs a signoff from an engineer.

Falon Land Studio LLC

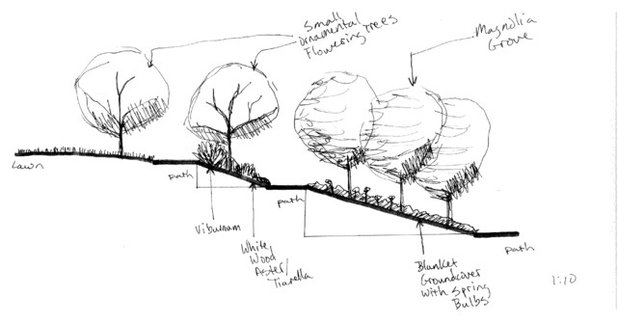

The sketch here is an initial concept section drawing for a winding, switchback-style path on a slope. The path weaves through new gardens at a gradual slope, so that it can be used for strolling and can be easily used by someone with limited mobility. On steep sites, stairs are not always preferable. The contours of the site can have a big impact on how you move through the landscape — especially where there are major grade changes across the site.

The shape of the ground has a large impact on spatial qualities. In the section drawing above, the sun’s cast was a major consideration. By winding a path through the gardens and planting new small trees that cast shade, a pleasant microclimate was made. In general, valleys and low points on a site are where fog, moisture and cool air will settle. Ridges and high points are where trees and structures are most exposed to winter wind and summer sun.

Paths, outdoor rooms and other various spaces are greatly impacted by the grading design. I use the term “grading design” because making a grading plan is both a technical and creative process; there are many different ways to shape the land. The basic stormwater functions must be met, but there’s also much expressive potential for how spaces can be defined through grading.

The photo here shows how the hill’s contours are elegantly shaped to create a ground that blends into the site and merges with the architecture. It is a fun example in which stairs and a sloped walkway are incorporated.

KAA Design

The problem areas in a grading plan often come back to basic stormwater runoff: erosion in steep areas and pooling water in flat areas. Grading for stormwater management is ultimately tied to the type of soil present. For example, the sandy soils in the flat terrain of coastal Florida rarely have problems with standing water, because the high sand content lets water drain freely. Inland parts of Florida, also with flat terrain but with richer organic soils that hold water, are more likely to have problems with standing water after a storm, because the soil does not drain as easily. Problem spots in the landscape must be managed as part of an overall grading plan, and not as isolated issues.

The steep slope in this image has been nicely designed with terraced steps and colorful plantings. The size of the steps helps to retain the slope, and the full plantings prevent soil erosion.

Read more about terraced plantings

Total Turf Landscaping

Grading Elements to Move WaterSlopes: Slopes are really at the heart of any grading plan for stormwater management. The slopes have to be managed to effectively move water. If they are too steep, you get major erosion (which is also influenced by soil type) or unstable landforms. If they are too gradual, water may collect in undesirable areas.

Swales: A swale is simply an elongated sloped depression that moves water. This image clearly shows a grassy swale at the top of a slope that moves away from the house. Swales can be expressed in many ways. At their simplest, they look like the swale in this image; more complex swales can be curvy, laid with stones, filled with plants or some combination of these things.

Drains: Drains are structures that lead to a subterranean structure, like a perforated drainpipe or an infiltration well. Drains are used mostly within or at the edges of paved areas to collect runoff from that area and move it away from the surface, where it is whisked away to the city sewer. Underground drainage systems of catch basins connected to pipes are an infrastructure-heavy way to manage stormwater. Instead, work with a landscape architect to create an overall grading plan that manages stormwater creatively with drains used in selective spots. A drain can also connect to a runnel or trench drain that directs water to an area for infiltration in the garden.

Landscape Plus, LLC

Other Stormwater Management ElementsPermeable paving. Stormwater runoff comes mostly from paved surfaces in the home landscape, and the driveway is usually a big one. The driveway here is covered with pavers that are designed to act as a permeable surface. They are strong enough for vehicles to drive over, but they have gravel between them so that water can pass through there.

Making hard surfaces permeable can work wonders, because it reduces overall stormwater runoff and therefore the need to move water by shaping the ground. Permeable surfaces are also graded, just like the ground, to be set at a consistent slope that works with the overall grading plan and site design.

See more ways to reduce runoff

microhouse

Rain gardens. One of the reasons rain gardens have become so popular is that they are very effective for infiltrating rainwater in home landscapes. You can direct roof runoff from your downspout to a swale that ends in a rain garden, or use a rain garden at the foot of a hill to collect runoff. The amazing thing about the ground is that it absorbs and cleanses water through the process of infiltration.

The more you can mimic the natural process of infiltration in your landscape, the fewer problems you will have in managing runoff. Even a lawn with a gradual (2 percent) slope and a good soil for infiltration will effectively let rainwater soak in. The size and location of a rain garden or an infiltration lawn will depend on your climate and annual rainfall. A landscape architect can advise you on the design of an infiltration area that fits within an overall grading plan.