“Large or small, [the garden] should be orderly and rich. It should be well fenced from the outside world. It should by no means imitate either the willfulness or the wildness of nature, but should look like a thing never to be seen except near the house. It should, in fact, look like part of the house.” — William Morris, Victorian designer, craftsman, poet and socialist writer, in his 1879 lecture, “Making the Best of It”

Though spoken in the 19th century, this could easily be a manifesto for how many of us like to design our own gardens today.

William Morris is considered to be the founder of the Arts and Crafts movement, which opposed changes taking place in the Industrial Revolution and championed craftsmanship versus factory production. In his houses and gardens, as well as the myriad products he designed and made in his business, Morris & Co, Morris was inspired by his love of medieval art and design, and by its tradition of craftsmanship.

The design of his gardens was very simple: straight paths, ordered rows of vegetables and straight borders overflowing with a riot of flowers. All was set in a landscape constructed of local materials and built by local craftspeople. The house and garden were one with the surrounding landscape.

Let’s look at some of Morris’ ideas and see whether they really are relevant to our gardens today.

HartmanBaldwin Design/Build

This is possibly the image of an Arts and Crafts garden that most of us have in our minds. Very English and cozy; busy with flowers restrained by low boxwood hedging.

But this is not William Morris’ style of garden — it takes its design features from the later Edwardian gardeners, such as Gertrude Jekyll.

Kelmscott Manor in the English Cotswolds is where Morris lived from 1871 until his death in 1896. It was his ideal of a house and garden. He called it his heaven on earth.

The house and garden are now run and owned by a charitable society, and both have been restored to how they were when Morris lived there.

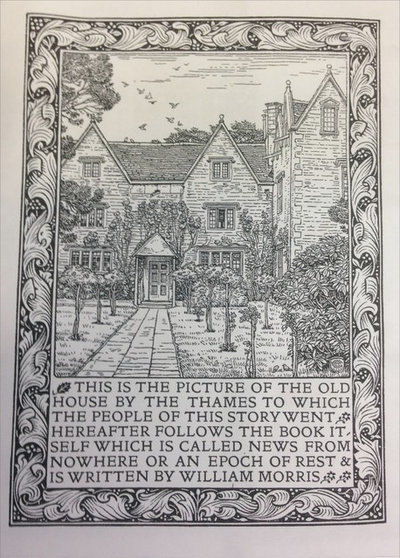

The best evidence of how the front garden of Kelmscott Manor looked in Morris’ time is from the title page of one of his books,

News from Nowhere. A straight flagstone path that leads to the front door is flanked by standard roses, not at all the vision we have of the Arts and Crafts garden.

gregory lens

This garden from today is almost a mirror image of Morris’ Kelmscott Manor garden. The line of plain, standard roses, not always an easy plant to use in garden design, performs the same task it did in Morris’ garden: It leads the eye to the front door.

Morris was upset by plant breeders of the time. He saw them as meddling with nature, especially with newer varieties of his favorite flower, the rose. He preferred his flowers to be simple and disliked changes to them, such as the trend of creating double flowers.

The Design Build Company

“ … should be orderly and rich.”This garden without doubt has a touch of Morris. Its straight brick path is blurred at its edging with rich plantings, while the retaining walls are a beautiful example of Morris’ love of craftsmanship. In the way the path at Kelmscott Manor leads to the front door, here the eye is lead to the simple white gateway.

All this was very different from the fashion of the day, which was carpet bedding; beds were planted in intricate patterns, formed from dozens of half-hardy plants. These plants, not being native to England, had to be nurtured in heated greenhouses until the weather was suitable for planting. Morris hated this. He preferred vernacular plants that had their roots mainly in the wildflowers he loved.

ROOMS & BLOOMS

“ … well fenced from the outside world …” Morris’ love of the medieval pointed him to the

hortus conclusus (Latin for “enclosed garden") as the blueprint for the design of his gardens. The gardens were enclosed by a wall and had straight pathways surrounded by symmetrical beds overflowing with cottage-garden-style plants.

Morris was firm in his belief that traditional wood and stone were the perfect materials for hard landscaping, as they help to link the garden with both the house and the surrounding landscape. He hated the iron fencing the Industrial Revolution had made more available to gardeners.

“ …

look like part of the house.”Morris promoted a return to craftsmanship in the garden and, as in his fabric and wallpaper designs, attention to detail was foremost.

Paintbox Garden

“ … by no means imitate either the willfulness or the wildness of nature.”As with his love of straight paths, Morris loved the same formality of vegetable gardens planted in ordered rows. Decades before the planting of Lawrence Johnson’s Hidcote Gardens, Morris’ garden at Kelmscott Manor was an early example of the idea of a garden’s being a series of exterior rooms, and one of these rooms was his well-ordered vegetable garden.

Laara Copley-Smith Garden & Landscape Design

Straight walks bordered by abundant plantings are returning to garden design, as we’ve seen at recent Chelsea Flower Shows.

The rear garden at Kelmscott Manor had such a walk. It was immortalized in the painting “The Long Walk at Kelmscott Manor,” by Marie Spartali Stillman. Morris filled his straight borders with simple cottage garden plants allowed to grow and find their own space.

Affecting Spaces

Does this contemporary garden tread in the footsteps of Morris? Consider that it is orderly, with straight lines and a formal layout, and well fenced. It is also far from the “wildness of nature”; it was planned carefully to be an outdoor continuation of the house. Morris strongly felt that garden design was about the domestic arts rather than horticulture, linking the garden to the house.

Your turn: Do you have any garden features inspired by William Morris? Share a photo in the Comments.